Events & Promotions

| Last visit was: 06 May 2024, 21:07 |

It is currently 06 May 2024, 21:07 |

Customized

for You

Track

Your Progress

Practice

Pays

10:30 AM EDT

-11:30 AM EDT

12:00 PM PDT

-11:00 PM PDT

08:30 AM PDT

-09:30 AM PDT

08:30 AM PDT

-09:30 AM PDT

08:00 PM PDT

-09:00 PM PDT

05:30 AM PDT

-07:30 AM PDT

11:00 AM IST

-01:00 PM IST

11:00 AM IST

-01:00 PM IST

| FROM Magoosh Blog: GMAT Analytical Writing: All About the GMAT Essay and How to Prepare For It |

Yup, the rumors are true: you’ll encounter a 30-minute GMAT analytical writing section on test day. But while analytical writing can seem tough at first, finding out exactly what’s expected and how to attack it for a maximum score will do a lot to make the GMAT essay feel manageable! In this post, we’ll take a look at what you need to know to master the GMAT AWA. Introduction to GMAT Analytical Writing[/*] [*]What to Expect for GMAT Analytical Writing[/*] [*]How to Approach the GMAT AWA (Strategy and Tips)[/*] [*]Breakdown by Section[/*] [*]Example GMAT Essays[/*] [*]Scoring for GMAT Analytical Writing[/*] [*]GMAT AWA and Business School[/*] [/list]   The first bullet point tells us: a good AWA essay is well-organized, has a natural flow from point to point, and is clear and unambiguous about what it is saying. Those are all important points to keep in mind. The second bullet point reminds us: what they present will be, in all likelihood, a flawed argument, but what you must create is a cogent and clear argument, and that will necessarily involve providing clear and relevant support. It’s not enough simply to assert something badly: you must provide justification for what you are saying. The final bullet points may appear enigmatic: “control the elements of standard written English.” What does that mean? Well, first of all, it means no grammar or syntax mistakes. It also means varying the sentence structure—some simple sentences (noun + verb), some with two independent clauses (noun + verb + and/but/or + noun + verb), some with dependent clauses, some with infinitive phrases, some with participial phrases, etc. Finally, it means choosing the right words and the right tone: the tone should be skeptical toward the prompt argument and persuasive toward the points you are making, but not arrogant or dogmatic in any way. The following paragraph always appears after the argument prompt. This is the real meat-and-potatoes of the AWA directions:  First of all, notice it give you one clear task: “Be sure to analyze the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument.” Then, it lists several strategies that you might employ in your analysis. Don’t feel compelled to use every one of these in every AWA essay, though you should be using most of them in most essays.  Recognizing assumptions is essential for the Critical Reasoning questions, and it will also serve you well on attacking the prompt argument in your AWA. [/*] [*]Know the Directions: This a matter not only of knowing what they say but also, more importantly, understanding the various options you have for analyzing the argument. This list of analytical strategies is always given in the paragraph that follows the prompt argument. It’s important to get familiar with this “analytical toolbox”, so it is yours to employ on test day.[/*] [*]Recognize the Common Flaw Patterns: GMAT AWA prompt arguments often contain one of six types of flaws. Learn to spot these patterns, so you are ready on test day.[/*] [*]Plan Before You Write: This is obvious to some test-takers. Your first task is to find objections to and flaws in the prompt argument. Create a list of flaws. Then, select the 2-4 of those that are most relevant, that would be the most persuasive talking points. Once you have your list of insightful flaws, then you are ready to write.[/*] [*]Use a Template: Many test takers find it helpful to have the basic structure of the AWA essay already planned out and practiced, so it’s just a matter of plugging in the specific details on test day. Here’s an example of a possible GMAT writing template. Feel free to adapt this template as is, modify it, or create one of your own.

In addition to variety in sentence structure, strive for variety in word choice. Of course, you will want to echo words that appear in the prompt argument. But in your own analysis, vary the descriptive words, never using the same word twice. Don’t say “weak … weak … weak” when you can say “unpersuasive … untenable … questionable.” Well-chosen synonyms can make an essay shine.[*]Avoid Common AWA Errors: There are a few common flaws that can pull your GMAT analytical writing score down. As you practice the AWA, make sure you avoid the following:

AWA brainstorming. As you brainstorm, list the argument’s flaws; then evaluate those flaws to find which objections are the strongest. Write an Introduction You don’t need to reinvent the wheel with each GMAT AWA introduction. Start by stating where the passage is from. Then, focus on two main tasks: summarizing the argument and stating why it’s flawed. Keep it short and sweet; three sentences are enough to get your main points set up! Construct Your Body Paragraphs These will make up the lion’s share of your essay, so you’ll spend most of your time writing body paragraphs. Here’s how to go about doing that:

First of all, keep in mind that you should not dwell in the conclusion. The heart of your essay, what really matters toward your score, is in the body paragraphs. These should be bulky and in-depth, but the conclusion should be short and to the point. Wrap things up in a timely manner so that you can get to the business of editing and revising your essay. To keep things manageable and short, don’t go into the details. You only need to recap the major problems in the argument. Sometimes it is enough to say that there are major problems in the argument. Ignore the desire to repeat all the main points that you covered in the body paragraphs. This will only take extra space and waste precious time. Finally, recommend a way to achieve the goal stated in the article. It is important to approach the analysis of the argument as an interested party. You don’t want to be wholly negative. For one, you will write a better analysis if you imagine yourself tied to the argument in some way, and two, the prompt asks you to strengthen the argument. Find some general evidence that will make the argument more convincing or make it irrefutable. Suggest a change so that the logic stands on firmer ground. examples of analytical questions for the GMAT, look no further! Once you’ve read few a through sample AWA prompts, read through the third prompt on page 31 of the PDF. Magoosh GMAT expert Mike McGarry has written a great GMAT AWA Example essay in response to this prompt, including analysis of why it works well and why it would receive a 6.  GMAT AWA scoring rubric you can use for this purpose. But if you’re not certain about how your essays measure up to the GMAT scale, there are other ways to get your GMAT essay scored. These include GMAT Write, an official (paid) service from GMAC; friends; and forums. Take a look and see what option works best for you.  recent evidence suggest that adcoms also rely on the IR score significantly more than the GMAT essay score. But while it’s true that, in your GMAT preparation, Quant and Verbal and even IR deserve more attention than the AWA, it’s also true you can’t completely neglect AWA. The difference between a 5 or 6 as your GMAT Analytic Writing score will not make or break a business school admission decision, but having an essay score below a 4 could hurt you. The purpose of the AWA is to see how well you write, how effectively you express yourself in written form. This is vital in the modern business world, where you may conduct extensive deals with folks you only know via email and online chatting. Some of your important contacts in your business career will know you primarily through your writing, and for some, your writing might be their first experience of you. You never get a second chance to make a first impression, and when this first impression is in written form, the professional importance of producing high-quality writing is clear. While you don’t need to write like Herman Melville, you need to be competent. A GMAT Analytic Writing score below 4 may cause business schools to question your competence. That’s why it’s important to have at least a decent showing in AWA. For Non-Native English Speakers In particular, if English is not your native language, I realize that this makes the AWA essay all the more challenging, but of course, a solid performance on the AWA by a non-native speaker would be a powerful testament to how well that student has learned English. Toward this end, non-native speakers should practice writing the AWA essay and try to get high-quality feedback on their essays. Devoting 30% or more of your available study time to AWA is likely unwise, but devoting 0% to AWA might also hurt you. Between those, erring on the low side would be appropriate. If, in a three-month span, you write half a dozen practice essays, and get generally positive feedback on them with respect to the GMAT standards, that should be plenty of preparation.  Conclusion The GMAT analytical writing can feel like a slog when you first encounter it: it requires deep focus and analysis, and it’s not what most students have spent their prep time working on. But with a bit of preparation, your GMAT essays can take your admissions file to the next level by boosting your AWA score significantly! By including GMAT writing in your overall GMAT prep schedule, you’ll ensure that this section of the test doesn’t become a drag on your application—and helps, rather than hurts, your shot at your dream school. Good luck! The post GMAT Analytical Writing: All About the GMAT Essay and How to Prepare For It appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: GMAT Arithmetic 101 |

The GMAT Quant section tests a variety of mathematical concepts, including algebra, geometry, and arithmetic. Generally speaking, the test-makers are not looking to trick or confuse you. Most GMAT math problems are rather straightforward. Read on to find out the specific arithmetic topics covered, tips for success, and plenty of practice problems! What kind of arithmetic is tested on the GMAT?[/*] [*]GMAT Arithmetic Tricks: 3 Tips for Success[/*] [*]GMAT Arithmetic Review: Practice Problems[/*] [*]Conclusion[/*] [/list] Arithmetic Operations[/*] [*]Number Properties[/*] [*]Fractions[/*] [*]Ratio and Proportions[/*] [*]Percents[/*] [*]Powers and Roots of Numbers[/*] [*]Statistics[/*] [*]Combinatorics (Counting Methods)[/*] [*]Discrete Probability[/*] [/list] Now let’s take a quick tour through these various areas. Some of the topics overlap a bit. And you may need to combine ideas to solve more challenging problems, but here are the basics. order of operations, or spotting common factors to cancel in complicated fractions. It’s important to have good number sense too. number properties. Primarily, we’re talking about properties of integers. So, be prepared to analyze evens and odds, consecutive integers and multiples, prime numbers, positives and negatives, and all the related concepts. For example, did you know that 1 is not a prime number? On the other hand, 0 is definitely an integer! fractions on the GMAT! GMAT Quantitative: Ratio and Proportions Understanding Percents on the GMAT[/*] [*]Percent Change Problems on the GMAT[/*] [*]GMAT Quant: Practice Problems with Percents[/*] [/list] Laws of Exponents and Roots will definitely help you to get through the GMAT Quantitative section. Here are a few links to get you started. But what about those “impossible” problems with huge tricky exponents, in which they ask for the units digit of the answer? Don’t fall into the trap of trying to work out the number exactly — that will eat up too much precious time. Instead, review these methods: GMAT Quant: Difficult Units Digits Questions. descriptive statistics and statistical significance. Often, the problems can be done without much of computation. For example, did you know that if you multiplied all of the data by the same number, \(k\), then the mean, median, mode, and standard deviation also gets multiplied by that same factor \(k\)? By contrast, adding the same number \(k\) to all of the data only changes the mean, median, and mode, while leaving the standard deviation the same!  Statistics make the world go ’round! (Image by Wynn Pointaux from Pixabay) factorials. Check out GMAT Permutations and Combinations for more! counting to geometric probability and problems based on dice, you have to be prepared for just about anything. But there are just a few fundamental concepts to keep in mind. The main idea behind probability is that it’s a fraction of the desired outcomes over the total number of outcomes. To get started, check out this article: GMAT Probability Rules. Also, you can expect probability to be a favorite topic for GMAT data sufficiency questions — for practice, see GMAT Data Sufficiency Practice Questions on Probability.   Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]\(\dfrac{4^6-4^5}{3} = \) (A) \(\dfrac{4}{3}\) (B) \(4^{4/3}\) (C) \(4^4 – 4^{5/3}\) (D) \(4^5 – 4^4\) (E) \(4^5\) Show Answer The answer is E. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]\(\sqrt{81+81+81+81+81+81+81+81} = \) (A) \(18\sqrt{2}\) (B) \(36\sqrt{2}\) (C) 72 (D) \(162\sqrt{2}\) (E) 648 Show Answer The answer is A. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]If \(k\) is a positive integer, what is the smallest possible value of \(k\) such that \(1040k\) is the square of an integer? (A) 2 (B) 5 (C) 10 (D) 15 (E) 65 Show Answer The answer is E. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]If \(k\) is the greatest positive integer such that \(3^k\) is a divisor of \(15!\) then \(k = \) (A) 3 (B) 4 (C) 5 (D) 6 (E) 7 Show Answer The answer is D. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]A certain school district has specified 5 different novels and 4 different non-fiction books from which teachers can choose to assemble a summer reading list. Each summer reading list must have exactly 3 novels and 2 non-fiction books. How many different summer reading lists are possible? (A) 54 (B) 60 (C) 72 (D) 120 (E) 240 Show Answer The answer is B. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [/list] Data Sufficiency Questions For each of the below problems, choose one of the following: (A) Statement 1 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 2 alone is NOT sufficient. (B) Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. (C) BOTH statements 1 and 2 TOGETHER are sufficient to answer the question, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. (D) Each statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question. (E) Statement 1 and 2 TOGETHER are NOT sufficient to answer the question. [*]Ann and Bob planted trees on Friday. What is the ratio of the number of trees that Bob planted to the number of trees that Ann planted? (1) Ann planted 20 trees more than Bob planted. (2) Ann planted 10 percent more trees than Bob planted. Show Answer The answer is (B) Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]If \(P\) and \(Q\) are positive integers, and if \(P > 1\), does \(P = Q\)? (1) \(P\) is a factor of \(Q\) (2) \(P\) is a multiple of \(Q\) Show Answer The answer is (C) BOTH statements 1 and 2 TOGETHER are sufficient to answer the question, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]What is the value of \(x\)? (1) \( (x-5)^2 = 0 \) (2) \( (x-3)^2 = 4 \) Show Answer The answer is (A) Statement 1 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 2 alone is NOT sufficient. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]A box contains only red chips, green chips, and blue chips. If a chip is randomly selected from the box, what is the probability that the chip is either red or green? (1) The probability of selecting a green chip is 1/3. (2) The probability of selecting a blue chip is 1/7. Show Answer The answer is (B) Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]In a certain group, the average (arithmetic mean) age of the males is 28, and the average age of the females is 30. If there are 100 people in the group, how many of them are males? (1) The average age of all 100 people is 28.9 (2) There are 10 more males than there are females. Show Answer The answer is (D) Each statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [*]A certain aquarium holds three types of fish: angelfish, swordtails, and guppies. What is the ratio of the number of guppies to the number of angelfish? (1) There are 200 fish in the aquarium (2) 45 percent of the fish are swordtails, and there are twice as many swordtails as there are angelfish. Show Answer The answer is (B) Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. Click here for the video explanation from our GMAT product. [/list]  GMAT Arithmetic 101 appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: 20 GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions and Answers |

Every time you put something into writing in a professional setting, it should represent you at your very best—and an important part of that is correct grammar. That’s why business schools care about it, which is why the GMAT tests it. The primary vehicle for testing grammar on the GMAT is the Sentence Correction questions. Keep reading to see what is tested on GMAT Sentence Correction, practice questions for SC, and tips for success. ? What is GMAT Sentence Correction?[/*] [*]How can I do well on SC?[/*] [*]How to Master Sentence Correction on GMAT [*]GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions with Explanations[/list]  GMAT Sentence Correction Strategies. While you’re thinking about strategy, here are some tips on how to ace GMAT sentence correction!  GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions is an excellent resource. It compiles links to other blog posts, listed by the rule that they have to do with. So, if you wanted to learn about gerunds and gerund phrases, or when to use like vs. as, you can go to a post that focuses on that rule with examples. In many ways, SC improvement takes time. You have to learn and re-learn grammar and style rules. This takes time, so be patient with yourself. Use the lesson videos, and make sure to learn from your practice. Also, your process of elimination skills need sharpening and training. The GMAT is a rapid and tricky test, and the more organized and purposeful prep that you do, the more likely it is that you’ll see an increase in your practice scores.  GMAT prep and are a good sample of the different sorts of questions you’re likely to see on your exam. Plenty of different grammar and style rule violations, problems with the structure and logical flow, and some examples of issues with idioms and phrasing.

The post 20 GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions and Answers appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: GMAT Sentence Correction with 20 Practice Questions and Answers |

Every time you put something into writing in a professional setting, it should represent you at your very best—and an important part of that is correct grammar. That’s why business schools care about it, which is why the GMAT tests it. The primary vehicle for testing grammar on the GMAT is the Sentence Correction questions. Keep reading to see what is tested on GMAT Sentence Correction, practice questions for SC, and tips for success. ? What is GMAT Sentence Correction?[/*] [*]How can I do well on SC?[/*] [*]How to Master Sentence Correction on GMAT [*]GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions with Explanations[/list]  GMAT Sentence Correction Strategies. While you’re thinking about strategy, here are some tips on how to ace GMAT sentence correction!  GMAT Sentence Correction Practice Questions is an excellent resource. It compiles links to other blog posts, listed by the rule that they have to do with. So, if you wanted to learn about gerunds and gerund phrases, or when to use like vs. as, you can go to a post that focuses on that rule with examples. In many ways, SC improvement takes time. You have to learn and re-learn grammar and style rules. This takes time, so be patient with yourself. Use the lesson videos, and make sure to learn from your practice. Also, your process of elimination skills need sharpening and training. The GMAT is a rapid and tricky test, and the more organized and purposeful prep that you do, the more likely it is that you’ll see an increase in your practice scores.  GMAT prep and are a good sample of the different sorts of questions you’re likely to see on your exam. Plenty of different grammar and style rule violations, problems with the structure and logical flow, and some examples of issues with idioms and phrasing.

The post GMAT Sentence Correction with 20 Practice Questions and Answers appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: Integrated Reasoning on the GMAT: The Complete Guide |

If you’re sitting down to your first GMAT Integrated Reasoning section, you might not know what to think! You’ll have 30 minutes to answer 12 Integrated Reasoning GMAT questions involving a ton of data analysis, critical thinking, and quantitative reasoning. But by preparing early—and thoroughly!—you’ll be able to get the Integrated Reasoning GMAT score that you want on test day. What is GMAT Integrated Reasoning? The GMAT Integrated Reasoning section tests your quant-based and verbal-based reasoning in 4 parts: multi-source reasoning, table analysis, two-part analysis, and graphics interpretation. Essentially, the GMAT IR section is testing for your data analysis skills. The big question for many students: just what is the GMAT IR score importance? IR is relatively important (and increasingly so!), so it’s vital not to ignore it! Overall, you can expect to see 12 questions in 30 minutes. It’s not quite as simple as it sounds, though: each graph or prompt will have multiple questions. In addition, you’ll have to answer a question before you can move on—and you can’t go back to a question once you’ve answered it.  Check out this video of Magoosh’s Introduction to Integrated Reasoning lesson! Integrated Reasoning Question Types on the GMAT Multi-Source Reasoning Multi-source reasoning questions show you a split screen: on the left, you’ll have three clickable cards, each with a piece of information that will help you answer a particular question, and which you can only see one of at a time. The questions are either standard five-choice multiple choice or multiple dichotomous choice. You’ll have two answer choices (e.g. “true/false”) for each part of a three-part question. For more sample multi-source reasoning problems, click here! Table Analysis Table analysis questions give you a sortable table of numbers. These are accompanied by multiple dichotomous choice questions, in which you have two answer choices (e.g. “true/false”) for each part of a three-part question. Check out a sample table analysis problem! Graphics Interpretation For graphics interpretation questions, you’ll receive some visual information in the form of a chart or a graph, then questions containing two drop-down menus each. These menus will have you fill in blanks within a sentence according to the data shown in the visual. Check out more sample graphics interpretation problems! Two-Part Analysis Two-part analysis questions give you a large prompt, followed by a question-and-answer table. You will fill out the answers for each of two questions, which can vary; they may be partially or completely related, but they will always be interdependent. Check out a sample two-part analysis problem! Strategies for Getting a Good Integrated Reasoning GMAT Score Getting a good Integrated Reasoning GMAT score can be tricky—not least of all because a lot of people aren’t sure what a good IR score is! Unlike the total GMAT score, which is scored between 200 and 800, IR is scored between 1 and 8. Most people would consider a good score to be above the 50th percentile—in other words, better than half of test-takers’ scores. For IR, this is a 5 or higher. So how do you get that good score of 5+ on GMAT IR? Here are a few keys to succeeding:

Need Integrated Reasoning GMAT practice? You’re not alone! That’s why Magoosh is excited to present you with the ultimate GMAT Integrated Reasoning eBook: Magoosh’s Complete Guide to GMAT Integrated Reasoning! Here, you’ll find detailed explanations and tips for each IR question type, as well as practice witin each area.   Still want more? You can find Magoosh’s guide to the official GMAT Integrated Reasoning practice here! A Final Note GMAT Integrated Reasoning questions are designed to throw a lot of data at you, fast. And while a lot of test-takers will let that throw them off their game, you can ensure that you’re all set for test day by familiarizing yourself with these question types and practicing, practicing, practicing! The more used to the question types you are, the easier your test day experience will be. And the GMAT IR prep tools in this post will help you get there. Good luck! The post Integrated Reasoning on the GMAT: The Complete Guide appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: GMAT Word Problems: Introduction, Strategies, and Practice Questions |

You may love GMAT word problems or you may hate them, but you can’t get around them if you want to ace the GMAT Quant section. No matter what your feelings are about this problem type, though, Magoosh’s experts have put together everything you need to know (and practice!) GMAT word problems in order to master them before test day. What to Expect from GMAT Word Problems[/*] [*]Strategy Guide: What’s the Trick to Mastering GMAT Word Problems?

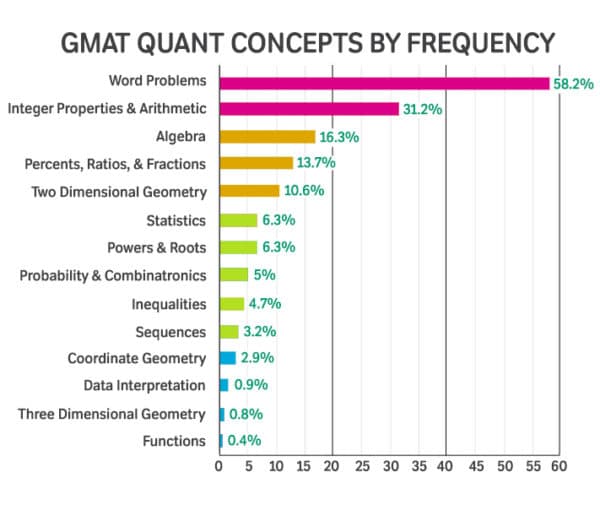

GMAT Quant section. How much of the GMAT is word problems? Within the Quant section, actually a whole lot! A study of official GMAT questions from actual tests show that word problems account for 58.2% of all GMAT math questions.  In other words, test-takers should anticipate a word problem cropping up (on average) in three out of every five questions you’ll see in Quant. Because of GMAT word problems’ prevalence, you can expect to see both Data Sufficiency and Problem Solving questions in this format. The question format and answer choices may look different, but the basic premise will be the same. You may be feeling the pressure, but hang in there! If you’re worried about how to master word problems on the GMAT, keep reading for our GMAT Word Problems strategy guide.  Variables in GMAT Answer Choices: 2 Approaches. tips for plugging in numbers that you should use! Here’s a quick summary of how to quick the best numbers for a particular problem:

Click here for a video answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 1![/b] Click here for a text answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 1! Our task is to determine the ratio of Bob’s trees to Ann’s trees. Let’s label these numbers of trees with variables: Bob’s trees→B, Ann’s trees→A With these variables, we can express the ratio we want to determine: \(B/A\) =? Statement 1: Ann planted 20 trees more than Bob planted. Let’s translate this into an equation using A and B: \( A=B+20 \) Now we can substitute this into our ratio, replacing A: \(B/A\) = \( B/(B+20) \) No matter what simplifications we make, we cannot find a numerical value for this fraction. We would need a value for B. We cannot determine the ratio. Statement 1 by itself is not sufficient. Statement 2: Ann planted 10 percent more trees than Bob planted. Let’s translate this into an equation using A and B: \(A=1.10 x B \) Again, let’s substitute this in for A in our ratio: \(B/A\) = \( B/(1.10B) \) = \(1/1.1 \) We found a value for the ratio of Bob’s trees to Ann’s trees. Statement 2 alone is sufficient. [*]The Townville museum was open for 7 consecutive days. If the number of visitors each day was 3 greater than the previous day, how many visitors were there on the first day? (1) There were a total of 126 visitors for the 7 days. (2) The number of visitors on the seventh day was three times the number of visitors on the first day. [/list] A. Statement 1 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 2 alone is NOT sufficient. B. Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. C. BOTH statements 1 and 2 TOGETHER are sufficient to answer the question, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. D. Each statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question. E. Statement 1 and 2 TOGETHER are NOT sufficient to answer the question. Click here for a video answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 2! Click here for a text answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 2! If x is the number of visitors on the first day, then: x = # of visitors on the 1st day x + 3 = # of visitors on the 2nd day x + 6 = # of visitors on the 3rd day x + 9 = # of visitors on the 4th day x + 12 = # of visitors on the 5th day x + 15 = # of visitors on the 6th day x + 18 = # of visitors on the 7th day 1) Adding up the number of visitors gives us: x + (x + 3) + (x + 9) + (x + 12) + (x + 15) + (x + 18) = 126 We could simplify and solve this for x. So Statement 1 is sufficient. 2) x + 18 = 3x Again, we can simplify this and solve for x. So Statement 2 is sufficient. Answer: (D) [*]Two teachers, Ms. Ames and Mr. Betancourt, each had N cookies. Ms. Ames was able to give the same number of cookies to each one of her 24 students, with none left over. Mr. Betancourt was also able to give the same number of cookies to each one of his 18 students, with none left over. If N > 0, what is the value of N? (1) N<100 (2) N > 50 [/list] A. Statement 1 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 2 alone is NOT sufficient. B. Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. C. BOTH statements 1 and 2 TOGETHER are sufficient to answer the question, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. D. Each statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question. E. Statement 1 and 2 TOGETHER are NOT sufficient to answer the question. Click here for a video answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 3! Click here for a text answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 3! This question is really about common multiples and the LCM (note that it is different than finding the set of all multiples, though!). If Ms. Ames can give each of her 24 students k cookies, so that they all get the same and none are left over, then 24k = N. Similarly, in Mr. Betancourt’s class, 18s = N. What are the common multiples of 18 and 24? 18 = 2×9 = 2×3×3 = 6×3 24 = 3×8 = 2×2×2×3 = 6×4 From the prime factorizations, we see that GCF = 6, so the LCM is LCM = 6×3×4 = 72 and all other common multiples of 18 and 24 are the multiples of 72: {72, 144, 216, 288, 360, …} Statement #1: if N<100, the only possibility is N = 72. This statement, alone and by itself, is sufficient. Statement #2: if N > 50, then N could be 72, or 144, or 216, or etc. Many possibilities. This statement, alone and by itself, is not sufficient. Answer = (A) [*]A certain zoo has mammals and reptiles and birds, and no other animals. The ratio of mammals to reptiles to birds is 11:8:5. How many birds are in the zoo? (1) there are twelve more mammals in the zoo than there are reptiles (2) if the zoo acquired 16 more mammals, the ratio of mammals to birds would be 3:1 [/list] A. Statement 1 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 2 alone is NOT sufficient. B. Statement 2 ALONE is sufficient to answer the question, but statement 1 alone is NOT sufficient. C. BOTH statements 1 and 2 TOGETHER are sufficient to answer the question, but NEITHER statement ALONE is sufficient. D. Each statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question. E. Statement 1 and 2 TOGETHER are NOT sufficient to answer the question. Click here for a video answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 4! Click here for a text answer and explanation to GMAT Word Problem 4! A short way to do this problem. The prompt gives us ratio information. Each statement gives use some kind of count information, so each must be sufficient on its own. From that alone, we can conclude: answer = D. This is all we have to do for Data Sufficiency. Here are the details, if you would like to see them. Statement (1): there are twelve more mammals in the zoo than there are reptiles From the ratio in the prompt, we know mammals are 11 “parts” and reptiles are 8 “parts”, so mammals have three more “parts” than do reptiles. If this difference of three “parts” consists of 12 mammals, that must mean there are four animals in each “part.” We have five bird “parts”, and if each counts as four animals, that’s 5*4 = 20 birds. This statement, alone and by itself, is sufficient. Statement (2): if the zoo acquired 16 more mammals, the ratio of mammals to birds would be 3:1 Let’s say there are x animals in a “part”—this means there are currently 11x mammals and 5x birds. Suppose we add 16 mammals. Then the ratio of (11x + 16) mammals to 5x birds is 3:1. (11x + 16)/(5x) = 3/1 = 3 11x + 16 = 3*(5x) = 15x 16 = 15x – 11x 16 = 4x 4 = x So there are four animals in a “part”. The birds have five parts, 5x, so that’s 20 birds. This statement, alone and by itself, is sufficient. Both statements are sufficient. Answer = D.  average speed to total distance traveled, from total time to total amount. The key now is to put them into practice. Jot down these techniques or bookmark this post so you can come back as you continue your practice with GMAT word problems. You can also check out our posts on compound interest and Venn diagrams for more practice with GMAT word problems. Good luck! This post was written with contributions from our Magoosh content creator, Rachel Kapelke-Dale. The post GMAT Word Problems: Introduction, Strategies, and Practice Questions appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: GMAT Error Log: The Key to GMAT Success (Free Template Included) |

Your GMAT journey will be both challenging and rewarding. You will have highs and lows. There will be days that will build your confidence and then other days you will want to forget about completely. We have all had those days: you are studying and you feel like you can’t get any question right. But before you crumble up that paper, wipe clean that dry erase board, or power down that computer, STOP! Document your struggles and capture that data! Why Keeping an Error Log is So Important Our mistakes are chock full of information about our test taking abilities, strategies, and more importantly, our habits. Whether you’re GMAT studying for the first time or preparing for a retake, a critical look at how we approach, solve, and check our work will not only direct us to which areas we should study next, but will make us conscious about the bad habits we exhibit every time we attempt a GMAT problem.  We are always told to review our questions after we complete practice problems and the best way to advance your skills is by using a GMAT Error Log! I know what you’re thinking: not another GMAT wonder tool you have to buy to achieve your goal score. We get it. The GMAT is not only taxing on you mentally, physically, and socially (no one wants to hang out with the guy with Critical Reasoning flashcards at the party), but the GMAT is also COSTLY! That’s the beauty of the GMAT Error Log—it’s a completely free tool! Even better, keep reading and I will share with you a template I use to save you time on finding one online. Yes, the power of self evaluating your GMAT progress can be yours with a few clicks of a mouse! How to Use an Error Log GMAT prep is broken down into three parts: Content, Problem Solving, & Testing. What I have seen that keeps test-takers from earning their top score is that they haven’t spent enough time in the Problem Solving stage. Test-takers would read 100% of the material and complete 4 to 5 practice CAT exams, but would only successfully complete 20-30% of all the questions on the Magoosh platform and even less when it comes to the Official Guide. Knowing the ratios of a 30-60-90 triangle, how to FOIL, or what is a noun is important, but you must drill these topics in various various ways to really understand these concepts and how to answer these questions on the exam. Taking CAT exams in isolation will not improve your score. It is in careful review and reflection is where you will develop skills and earn points. CAT exams are a major time investment and are extremely valuable, so you don’t want to waste too much time to only answer 30 or more random questions. What I have seen successful test-takers do is create mini problems sets (5, 8, 10, or 16 questions) and use those as a sample test to gauge their skill set. In these practice problems is where the GMAT Error Log shines!  Let’s say each day for a week, you complete 10 to 20 random problems of various question types and difficulties. You are bound to miss a few questions. What most people do when they get a question wrong is read the explanation, say “oh I got it,” and move on. Here is where you leverage the GMAT Error Log. Not only will you read the explanation, you will also input the question you got wrong in the Error Log, what you did wrong, and what you will do differently next time. This seems like a small task today, but in the beginning, it can feel very daunting. After about 20 or so questions, though, you will get into the habit of updating your error log and begin to see the fruits of your labor. Leading up to a test day, a great Error Log can be a great review tool right before a CAT exam. When I work with my test-takers I teach them how to build a detailed Error Log with great care because it is those careless errors or habits that are written in the Error Log that jumps your GMAT score from a 620 to 650 or 690 to that 700. How to Structure Your GMAT Log Your Error Log does not need to have many bells and whistles. It doesn’t need to be something with macros and automated graphic generators. It doesn’t have to be a spreadsheet or digital at all. I actually keep two logs – an old school black and white marble notebook and a digital copy. The Error Log just has to fit your method of note-taking and meet your dedication to the process. Error Logs lose value when they are not updated. You only get out of the Error Log what you put in. I can never guarantee your score to improve, but I can say that having a running list of all your mistakes can help prevent you from making them again. Here is the key information you want to have in any GMAT Error Log:

This sounds extremely simple, because it is – the challenging part is sticking to the habit. After a few weeks, you will have an error log that you will cherish and will be excited to fill it up. So go out there and make some GMAT mistakes! I am here to help you—feel free to comment below and include a copy of your own error log and I will provide you some feedback and additional examples. The post GMAT Error Log: The Key to GMAT Success (Free Template Included) appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: Build Your Own GMAT Study Schedule |

You may have heard that studying for the GMAT is similar to preparing for a marathon. Not many people could run 26.2 miles (42.195 kilometers) without months of preparation! Though you probably won’t be as sweaty as you would be if you were to run for hours, you’ll still need endurance, speed, and strong mental skills to get through the GMAT with the score you deserve. Now, if you’re planning to run a marathon, your schedule is easy to fill out — It’s running on Monday, Tuesday probably some running, and then more running on Wednesday, Thursday, and so on. Not so simple with the GMAT! On your big day, you need to be prepared to use dozens of different math and grammar rules, track the meaning of several thousand words of text, and solve math problems with no calculator, all while going really fast and not making any mistakes. So more like a three-legged hot yoga CrossFit marathon. So what’s your plan? If you’re looking for some help deciding what to do each Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday to be ready for the unique challenges of the GMAT, you’ve found it! Once you have a goal in mind, and you’ve gathered some helpful resources, it’s time to start building your own GMAT study schedule. Stay motivated — know your goals What are your hopes and dreams? Who are you and who do you aspire to be? Sorry, I didn’t mean to get too personal, but some reflecting on your reasons for studying for a 3+ hour exam that costs hundreds of dollars and determines a big part of your future is a great place to start! If you need some ideas, consider your short term vs. your long term goals. Your short term goal might be to take the GMAT in 3 months and score 750, but your long term goal might be to get into a top MBA program and then conquer the world of finance (or maybe just prove to your old calculus professor that you are worth more than the Σ of your parts). I recommend writing down your goals and keeping them somewhere visible — on the fridge, the mirror, or out on your desk. When you’re feeling discouraged or especially tired, look back to your goals to reinvigorate you and remind you of why you’re putting yourself through this. Before you get started Before you start building your own GMAT study schedule, you’ll need to get squared away with a couple initial steps. The schedule builder will use a little info to guide you to a recommended study schedule template. Most importantly, it wants to know the results from your diagnostic tests. If you haven’t had all that fun yet, take about an hour and complete both the quantitative and verbal diagnostic tests. Then head back here and you’ll be ready to go. Build your custom GMAT study schedule After you’ve completed your diagnostic, just take this brief quiz and then we’ll recommend a template of your study schedule to get started with! powered by Typeform The post Build Your Own GMAT Study Schedule appeared first on Magoosh GMAT Blog. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems |

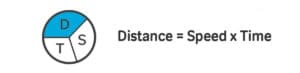

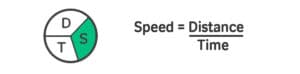

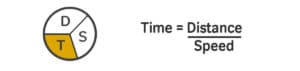

Word Problems make up a majority of the quantitative section of the GMAT (almost 60 percent). Of the word problems they’ll face, students tend to need the most help with GMAT motion problems. This type of problem centers around the “dust” formula, which is short for Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(\text{D}\times\text{S}=\text{T}\). But there are many varieties of motion problem, and we will discuss techniques for each of them. At the end of this article, you’ll also find motion word problems with solutions for you to test your knowledge! The Distance Equation[/*] [*]Multi-Segment Motion Problems[/*] [*]Average Speed[/*] [*]Multiple Traveler Questions[/*] [*]Shrinking and Expanding Gaps[/*] [*]Data Sufficiency[/*] [*]GMAT Motion Problems Review: Practice Problems[/*] [/list] Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(\text{D}\times\text{S}=\text{T}\). If you learn this basic equation well, you’ll be able to dust your math troubles away! (Insert rimshot.) We can rearrange this formula to determine that Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time, and that Time is equal to Distance divided by Speed. Distance is the measurement of how far apart objects, people, or points are. Speed is the rate at which someone or something is traveling. Time is how long it takes to travel. Let’s demonstrate this. Walking at a constant rate of 160 meters per hour, Monroe can cross a bridge in 2 hours. What is the length of the bridge? Here, the length of the bridge is the distance Monroe must cross. Using Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, we get: \((160\;\text{meters per hour})\times(2\;\text{hours})=320\;\text{meters}\) Seems simple enough so far, right? Let’s check out a few more GMAT motion problems.   Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time. Let’s take that a step further and talk about average speed. Average speed is defined as total distance traveled divided by the total time period spent traveling. This means that if you have a trip with multiple segments, you’ll want to take the sum of the distances of each segment and divide that by the sum of the times of each segment. Average speed captures the constant speed needed to travel the total distance in the total time. Let’s demonstrate this. Koki drove 16 miles in 10 minutes, and then drove an additional 6 miles in 5 minutes. What is Koki’s average speed for the entire trip in miles per hour? Click here for the answer and explanation Well, average speed is the total distance divided by the total time. \(\text{D}_\text{Total}=16\;\text{miles}+6\;\text{miles}=22\;\text{miles}\) \(\text{T}_\text{Total}=10\;\text{minutes}+5\;\text{minutes}=15\;\text{minutes}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{D}_\text{Total}}{\text{T}_\text{Total}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{22\;\text{miles}}{15\;\text{minutes}}\times\frac{60\;\text{minutes}}{1\;\text{hour}}=88\;\text{miles per hour}\) That’s straightforward enough, but what if we are not given any distances or times? It is possible to solve an average speed problem, even if all you are given are the different speeds in each segment of the trip. You might then think that average speed would just be the average of all of the speeds, but that is not correct. Let’s say that Nathaniel drove from Gwenville to Samton at an average speed of 24 miles per hour. He then drove the same route on the return trip back from Samton to Gwenville at an average speed of 36 miles per hour. If you were asked to find Nathaniel’s average speed, it would not just be 30 miles per hour (the average of 24 and 36). Click here to work through this problem To see this, let’s go back to our MVP dust formula. Since there are two legs of the trip, we will have two equations. D1, S1, T1; D2, S2, T2. Because Nathaniel’s trip is a round trip, we can assume that D1and D2 are the same, so we will set both of them equal to D. \(\text{D}_1=\text{D}\\\text{S}_1=24\;\text{miles per hour}\\\text{T}_1=\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{D}_2=\text{D}\\\text{S}_2=36\;\text{miles per hour}\\\text{T}_2=\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{D}_\text{Total}=\text{2D}\) \(\text{T}_\text{Total}=\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}+\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{D}_\text{Total}}{\text{T}_\text{Total}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{2D}}{\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}+\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}}\) We can factor a D out of this fraction. \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{1}{24}+\frac{1}{36}}\;\text{miles per hour}\) We can find a common denominator between 24 and 36. \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{3}{72}+\frac{2}{72}}\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{5}{72}}\;\text{miles per hour}=\frac{2}{1}\times\frac{72}{5}=\frac{144}{5}\;\text{miles per hour}=28.8\;\text{miles per hour}\) In summary, whenever you want to find the average speed of a round trip, and you are given the two segment speeds, you can put it in the form \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{2}}{\frac{1}{\text{S}_1}+\frac{1}{\text{S}_2}}\). You can also use this formula to find one of the segment speeds, given the other segment speed and the average speed.   diagram. Let’s say that a car and truck are moving in the same direction on the same highway. The truck is moving at 50 miles an hour, and the car is traveling at a constant speed. At 3 pm, the car is 30 miles behind the truck and at 4:30 pm, the car overtakes and passes the truck. What is the speed of the car? Click here for the answer and explanation The car and truck are moving in the same direction, and the car is gaining on the truck. This means that the gap between the vehicles is shrinking and that the gap rate is the difference of the two vehicles’ respective speeds. \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\text{S}_\text{C}-\text{S}_\text{T}\) The distance of the gap is initially 30 miles. \(\text{D}=30\;\text{miles}\) The time frame we are given for the closing of the gap is from 3 pm to 4:30 pm. \(\text{T}=1.5\;\text{hours}=\frac{3}{2}\;\text{hours}\) \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\frac{\text{D}}{\text{T}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\frac{30\;\text{miles}}{\frac{3}{2}\;\text{hours}}=30\times\frac{2}{3}=20\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(20\;\text{miles per hour}=\text{S}_\text{C}-50\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(20\;\text{miles per hour}+50\;\text{miles per hour}=\text{S}_\text{C}=70\;\text{miles per hour}\)  data sufficiency question from Magoosh, then review the video explanation.[/*] [/list]   Let us know how you did on these practice questions in the comments below. If you’re looking for more GMAT motion problems, try out one of Magoosh’s GMAT plans, which comes with practice tests, video lessons, and study schedules. Good luck! The post How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems appeared first on Magoosh Blog — GMAT® Exam. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems |

Word Problems make up a majority of the quantitative section of the GMAT (almost 60 percent). Of the word problems they’ll face, students tend to need the most help with GMAT motion problems. This type of problem centers around the “dust” formula, which is short for Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(\text{D}\times\text{S}=\text{T}\). But there are many varieties of motion problem, and we will discuss techniques for each of them. At the end of this article, you’ll also find motion word problems with solutions for you to test your knowledge! The Distance Equation[/*] [*]Multi-Segment Motion Problems[/*] [*]Average Speed[/*] [*]Multiple Traveler Questions[/*] [*]Shrinking and Expanding Gaps[/*] [*]Data Sufficiency[/*] [*]GMAT Motion Problems Review: Practice Problems[/*] [/list] Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(\text{D}\times\text{S}=\text{T}\). If you learn this basic equation well, you’ll be able to dust your math troubles away! (Insert rimshot.) We can rearrange this formula to determine that Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time, and that Time is equal to Distance divided by Speed. Distance is the measurement of how far apart objects, people, or points are. Speed is the rate at which someone or something is traveling. Time is how long it takes to travel. Let’s demonstrate this. Walking at a constant rate of 160 meters per hour, Monroe can cross a bridge in 2 hours. What is the length of the bridge? Here, the length of the bridge is the distance Monroe must cross. Using Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, we get: \((160\;\text{meters per hour})\times(2\;\text{hours})=320\;\text{meters}\) Seems simple enough so far, right? Let’s check out a few more GMAT motion problems.   Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time. Let’s take that a step further and talk about average speed. Average speed is defined as total distance traveled divided by the total time period spent traveling. This means that if you have a trip with multiple segments, you’ll want to take the sum of the distances of each segment and divide that by the sum of the times of each segment. Average speed captures the constant speed needed to travel the total distance in the total time. Let’s demonstrate this. Koki drove 16 miles in 10 minutes, and then drove an additional 6 miles in 5 minutes. What is Koki’s average speed for the entire trip in miles per hour? Click here for the answer and explanation Well, average speed is the total distance divided by the total time. \(\text{D}_\text{Total}=16\;\text{miles}+6\;\text{miles}=22\;\text{miles}\) \(\text{T}_\text{Total}=10\;\text{minutes}+5\;\text{minutes}=15\;\text{minutes}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{D}_\text{Total}}{\text{T}_\text{Total}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{22\;\text{miles}}{15\;\text{minutes}}\times\frac{60\;\text{minutes}}{1\;\text{hour}}=88\;\text{miles per hour}\) That’s straightforward enough, but what if we are not given any distances or times? It is possible to solve an average speed problem, even if all you are given are the different speeds in each segment of the trip. You might then think that average speed would just be the average of all of the speeds, but that is not correct. Let’s say that Nathaniel drove from Gwenville to Samton at an average speed of 24 miles per hour. He then drove the same route on the return trip back from Samton to Gwenville at an average speed of 36 miles per hour. If you were asked to find Nathaniel’s average speed, it would not just be 30 miles per hour (the average of 24 and 36). Click here to work through this problem To see this, let’s go back to our MVP dust formula. Since there are two legs of the trip, we will have two equations. D1, S1, T1; D2, S2, T2. Because Nathaniel’s trip is a round trip, we can assume that D1and D2 are the same, so we will set both of them equal to D. \(\text{D}_1=\text{D}\\\text{S}_1=24\;\text{miles per hour}\\\text{T}_1=\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{D}_2=\text{D}\\\text{S}_2=36\;\text{miles per hour}\\\text{T}_2=\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{D}_\text{Total}=\text{2D}\) \(\text{T}_\text{Total}=\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}+\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{D}_\text{Total}}{\text{T}_\text{Total}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{2D}}{\frac{D}{24\;\text{miles per hour}}+\frac{D}{36\;\text{miles per hour}}}\) We can factor a D out of this fraction. \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{1}{24}+\frac{1}{36}}\;\text{miles per hour}\) We can find a common denominator between 24 and 36. \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{3}{72}+\frac{2}{72}}\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{2}{\frac{5}{72}}\;\text{miles per hour}=\frac{2}{1}\times\frac{72}{5}=\frac{144}{5}\;\text{miles per hour}=28.8\;\text{miles per hour}\) In summary, whenever you want to find the average speed of a round trip, and you are given the two segment speeds, you can put it in the form \(\text{S}_\text{Average}=\frac{\text{2}}{\frac{1}{\text{S}_1}+\frac{1}{\text{S}_2}}\). You can also use this formula to find one of the segment speeds, given the other segment speed and the average speed.   diagram. Let’s say that a car and truck are moving in the same direction on the same highway. The truck is moving at 50 miles an hour, and the car is traveling at a constant speed. At 3 pm, the car is 30 miles behind the truck and at 4:30 pm, the car overtakes and passes the truck. What is the speed of the car? Click here for the answer and explanation The car and truck are moving in the same direction, and the car is gaining on the truck. This means that the gap between the vehicles is shrinking and that the gap rate is the difference of the two vehicles’ respective speeds. \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\text{S}_\text{C}-\text{S}_\text{T}\) The distance of the gap is initially 30 miles. \(\text{D}=30\;\text{miles}\) The time frame we are given for the closing of the gap is from 3 pm to 4:30 pm. \(\text{T}=1.5\;\text{hours}=\frac{3}{2}\;\text{hours}\) \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\frac{\text{D}}{\text{T}}\) \(\text{S}_\text{G}=\frac{30\;\text{miles}}{\frac{3}{2}\;\text{hours}}=30\times\frac{2}{3}=20\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(20\;\text{miles per hour}=\text{S}_\text{C}-50\;\text{miles per hour}\) \(20\;\text{miles per hour}+50\;\text{miles per hour}=\text{S}_\text{C}=70\;\text{miles per hour}\)  data sufficiency question from Magoosh, then review the video explanation.[/*] [/list]   Let us know how you did on these practice questions in the comments below. If you’re looking for more GMAT motion problems, try out one of Magoosh’s GMAT plans, which comes with practice tests, video lessons, and study schedules. Good luck! The post How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems appeared first on Magoosh Blog — GMAT® Exam. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: Everything You Need to Know about Getting an MBA |

An MBA, or a “Masters of Business Administration,” is a postgraduate degree achieved after an MBA candidate successfully goes through a business-focused program, usually lasting 1 to 2 years, and can be full-time or part-time. MBA programs are intended to better prepare you for business management skills and to make graduates more competitive in applying for leadership roles, or to crack into popular and high-paying industries, like tech, high-finance, and consulting. Check out our answers to frequently asked questions about the MBA below! What Is an MBA? [*]What Are the Benefits of an MBA?[*]What Do MBAs Cost?[*]How Hard Is an MBA?[*]Who Is an Ideal MBA Candidate?[*]How Do I Apply for MBA Programs?[*]When Should I Start Applying for an MBA?[/list]  full-time and part-time MBA as both went through the same academic rigors. Online MBA Programs This is the broadest category here, as “online MBAs” could very well be EMBAs, full-time or part-time. Generally, the feature is in the name: it’s online, rather than in-person, but there are some hybrids. Scholarships, as noted above, are more plentiful for full-time in-person programs. Your mileage here will vary depending on the university, as many programs have deep wells of experience in facilitating connections and learning online, but others are a little newer to the scene and adapting to the increasing trend to move online.

Joint Degree Programs Best for those who have a more defined post-MBA career path, joint-degrees have an industry-focus or field-focus. For example, Stanford has joint degrees focusing on education and business, while Darden has MD/MBA programs for those who are studying to be trained doctors and who need business skills. Graduates tend to be younger (24 to 30) and prefer full-time studies, as this degree is meant to gain access into a certain field by combining studies and credentials.  data on top-10 programs is abundant (hovering around $150,000 on average), but it’s a little more diffuse with other programs. Statistics for schools with lower rankings are less reliable but show an average of $50,000. That does not mean necessarily that the MBA world is bifurcated, but rather that there is a fairly broad spectrum. Also, it does mean that location matters and you should do your research on programs first based on fit, and then do digging into the benefits.[/list] [*]Network – For many, this is the indisputable top benefit of an MBA course, which should definitely be weighed when considering online programs. You have access to an alumni network regardless (formally, through the university, and informally through shared bonds that are more likely to get you to connect with alumni in your chosen field).[/list] [*]Higher employment rate – This is very program-specific, but generally, there is a higher chance of being employed consistently with an MBA. What is less clear, however, is the data behind their figures, which we’ll discuss a bit later here.[/list] [*]Access to higher-paying roles – The highest-paying roles after graduation tend to be (in descending order of average pay): consulting, financial services, and tech. What is also interesting is that those who get an MBA have the biggest salary increases in these industries (again, in order): consulting, food/beverage, investment management, and private equity, averaging $40,000 higher salary per year after graduation.[/list] On their own websites, MBA programs also highlight tangential benefits like increased confidence, better personal financial management, time-management skills, and broader worldview, but the data they used to gather such insights tends to focus on the gains in the careers and skills of those who ultimately decided to get an MBA. In other words, for those that decided it was worth it, it ended up being worth it. What is missing from their research are the trajectories of those who decided on an MBA alternative, but those data are inherently hard to come by – as we don’t have a reliable A/B test to understand what would have happened had they gone a different route. That means that MBA programs say MBAs are worth it, but you should definitely dig deeper to make sure they’re right for you.  average debt accumulated from an MBA course is near $100,000, and so, most students are in fact paying a steep price for the programs. Given the hefty tuition costs, you’re probably wondering if the MBA is truly worth it. That’s a topic for another post, but let’s just focus on the financial aspect of it. There are various rules of thumb for deciding this, but one that is fairly reasonable is this: the bump in compensation you expect in your first three years as an MBA graduate should cover the out-the-door cost of the MBA. For example, if you paid 160,000 for a full-time MBA, but your post-MBA salary went from 90,000 to 110,000, you very well might want to give it a long, hard look to see if it was worth the cost (160,000 – 20,000×3 > 0) – as you have a deficit of 100,000 and likely a high-interest student loan capping your appetite for career mobility in the meantime. Conversely, if your post-MBA salary was up from 90,000 to 150,000 with a 160,000 price tag, now you’re looking at a much stronger business case (160,000 – 60,000×3 < 0), as that salary is now covering more 20,000 more than the cost of the program itself. Rough math? Yes. Hard to calculate future salary? Of course! The key point to take away here is to think of the MBA as any savvy business person would: what is the probable ROI (return on investment) and what is the opportunity cost? In other words, ask yourself: will it be worth its cost, and what else could I be doing at the same time? You’ll also be spending at least a year on the degree itself and likely 100+ hours on the application itself, so time is also a consideration.  and in 2020, which is when many professionals decide that they’d like to boost their credentials and skills during a time with more uncertainty. Acceptance rates for universities have gone down recently due to an influx of applicants, hovering around 5% for most top-10 programs, for example.   short-list of schools, the easiest way to apply is to fill out the application online on the specific program’s website. Luckily, it appears that, while the details can change, the portal in which you’ll put your information is very similar across most colleges. In addition to your undergraduate degree and transcripts from your degrees (likely going back to high school), here are additional admissions requirements and their considerations: Two letters of reference: Please check the university itself for the format, but luckily this tends to be uniform: (1) describe your relationship to the candidate, and (2) how do they compare to their peers. You can probably tell that this has a distinct bias for managers. It may feel awkward to ask your current employer for a recommendation, so clients, former managers, and professors could also be options. You will then need to give the contact information for your recommenders, who will then be emailed a link to fill in a page with their letter and often to answer questions about your aptitude (on a score from 1-9, with 9 being the highest, for each indicator). GMAT/GRE score (or an Executive Assessment for EMBAS): Check the requirements for your program, as some schools will even accept “expired” GMAT scores (older than 5 years). TOEFL or IELTS score: If your undergrad was not taught in English, it’s likely that you’ll be required to provide a TOEFL or IELTS score. This is program-specific, and some have loosened their requirement to look at other representations of English ability. Admissions essays: The typical essays are “Why ____ program” and “Tell us about you,” but the recent trend has been for universities has been to ask more unique questions (see Duke’s “25 random things about yourself” essay, for example). There is also an “essay” asking for any additional information, which is an opportunity to talk about mitigating factors and other considerations but is not typically written in an essay-like way as the others. Most programs expect a simple bullet-point list for the “Anything else” essay. An application fee: Fees can range from $50 to $300 but the idea is that each application is given consideration and so this covers the university’s overhead. Be sure to look up the university’s “fee waiver” for which many program applicants can qualify. And the last thing you’ll need? Patience. For larger programs, it can take two or more months to hear back about interviews, but luckily their timelines are transparently communicated on their websites. It’s well worth it to first learn about programs, and then to mark the major dates in your calendar.  need more time to increase your GMAT score. For the overwhelming majority of programs that begin in the Fall, your rough timeline is: Round 1 Deadlines: June to September of the preceding year (for example, a 2022 to 2023 program will close applications in Summer 2021). Start preparing your application in February. Round 2 Deadlines: December to February before the program (for example, a 2022 to 2023 program will close applications in the preceding Winter). Start preparing your application by September. Round 3 Deadlines: March to May of the same year (for example, a 2022 to 2023 program will close applications in Summer 2022). Start preparing your application in December. While we’re on the subject, you might be wondering in which round you should apply. That’s a tough question, but overall the rule is “the earlier, the better,” as Round 2 tends to have more applicants than Round 1 and more in Round 3 than 2. The tough situation in which many applicants find themselves is weighing between Round 3 of this year or Round 1 of next year. For that, we don’t have an easy answer, but the question you should ask yourself is: will my application be substantially better in three months?  What You Need to Know about MBAs: A Summary An MBA can be valuable for your career, but it will likely come with a considerable price tag and 1-2 years of study (on top of around 3 months of preparation), so it’s well worth doing research and some serious introspection with the question: is this right for me? Also keep in mind that not all MBA programs are made the same, as there are degrees that may very well be more tailored to your career interests, or perhaps, frankly, none at all! If you’ve made it this far, congratulate yourself for doing research into what is right for you, and we wish you luck on whatever next steps you take. Let us know in the comments, are you planning on getting an MBA? The post Everything You Need to Know about Getting an MBA appeared first on Magoosh Blog — GMAT® Exam. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems |

Word Problems make up a majority of the quantitative section of the GMAT (almost 60 percent). Of the word problems they’ll face, students tend to need the most help with GMAT motion problems. This type of problem centers around the “dust” formula, which is short for Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(text{D}timestext{S}=text{T}\). But there are many varieties of motion problem, and we will discuss techniques for each of them. At the end of this article, you’ll also find motion word problems with solutions for you to test your knowledge! The Distance Equation[/*] [*]Multi-Segment Motion Problems[/*] [*]Average Speed[/*] [*]Multiple Traveler Questions[/*] [*]Shrinking and Expanding Gaps[/*] [*]Data Sufficiency[/*] [*]GMAT Motion Problems Review: Practice Problems[/*] [/list] Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, or \(text{D}timestext{S}=text{T}\). If you learn this basic equation well, you’ll be able to dust your math troubles away! (Insert rimshot.)  We can rearrange this formula to determine that Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time.  And Time is equal to Distance divided by Speed.

Let’s demonstrate this. Walking at a constant rate of 160 meters per hour, Monroe can cross a bridge in 2 hours. What is the length of the bridge? Here, the length of the bridge is the distance Monroe must cross. Using Distance equals Speed multiplied by Time, we get: \((160;text{meters per hour})times(2;text{hours})=320;text{meters}\) Seems simple enough so far, right? Let’s check out a few more GMAT motion problems.   Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time. Let’s take that a step further and talk about average speed. Average speed is defined as total distance traveled divided by the total time period spent traveling. This means that if you have a trip with multiple segments, you’ll want to take the sum of the distances of each segment and divide that by the sum of the times of each segment. Average speed captures the constant speed needed to travel the total distance in the total time. Let’s demonstrate this. Koki drove 16 miles in 10 minutes, and then drove an additional 6 miles in 5 minutes. What is Koki’s average speed for the entire trip in miles per hour? Click here for the answer and explanation Well, average speed is the total distance divided by the total time. \(text{D}_text{Total}=16;text{miles}+6;text{miles}=22;text{miles}\) \(text{T}_text{Total}=10;text{minutes}+5;text{minutes}=15;text{minutes}\) \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{text{D}_text{Total}}{text{T}_text{Total}}\) \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{22;text{miles}}{15;text{minutes}}timesfrac{60;text{minutes}}{1;text{hour}}=88;text{miles per hour}\) That’s straightforward enough, but what if we are not given any distances or times? It is possible to solve an average speed problem, even if all you are given are the different speeds in each segment of the trip. You might then think that average speed would just be the average of all of the speeds, but that is not correct. Let’s say that Nathaniel drove from Gwenville to Samton at an average speed of 24 miles per hour. He then drove the same route on the return trip back from Samton to Gwenville at an average speed of 36 miles per hour. If you were asked to find Nathaniel’s average speed, it would not just be 30 miles per hour (the average of 24 and 36). Click here to work through this problem To see this, let’s go back to our MVP dust formula. Since there are two legs of the trip, we will have two equations. D1, S1, T1; D2, S2, T2. Because Nathaniel’s trip is a round trip, we can assume that D1and D2 are the same, so we will set both of them equal to D. \(text{D}_1=text{D}\text{S}_1=24;text{miles per hour}\text{T}_1=frac{D}{24;text{miles per hour}}\) \(text{D}_2=text{D}\text{S}_2=36;text{miles per hour}\text{T}_2=frac{D}{36;text{miles per hour}}\) \(text{D}_text{Total}=text{2D}\) \(text{T}_text{Total}=frac{D}{24;text{miles per hour}}+frac{D}{36;text{miles per hour}}\) \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{text{D}_text{Total}}{text{T}_text{Total}}\) \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{text{2D}}{frac{D}{24;text{miles per hour}}+frac{D}{36;text{miles per hour}}}\) We can factor a D out of this fraction. \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{2}{frac{1}{24}+frac{1}{36}};text{miles per hour}\) We can find a common denominator between 24 and 36. \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{2}{frac{3}{72}+frac{2}{72}};text{miles per hour}\) \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{2}{frac{5}{72}};text{miles per hour}=frac{2}{1}timesfrac{72}{5}=frac{144}{5};text{miles per hour}=28.8;text{miles per hour}\) In summary, whenever you want to find the average speed of a round trip, and you are given the two segment speeds, you can put it in the form \(text{S}_text{Average}=frac{text{2}}{frac{1}{text{S}_1}+frac{1}{text{S}_2}}\). You can also use this formula to find one of the segment speeds, given the other segment speed and the average speed.   diagram. Let’s say that a car and truck are moving in the same direction on the same highway. The truck is moving at 50 miles an hour, and the car is traveling at a constant speed. At 3 pm, the car is 30 miles behind the truck and at 4:30 pm, the car overtakes and passes the truck. What is the speed of the car? Click here for the answer and explanation The car and truck are moving in the same direction, and the car is gaining on the truck. This means that the gap between the vehicles is shrinking and that the gap rate is the difference of the two vehicles’ respective speeds. \(text{S}_text{G}=text{S}_text{C}-text{S}_text{T}\) The distance of the gap is initially 30 miles. \(text{D}=30;text{miles}\) The time frame we are given for the closing of the gap is from 3 pm to 4:30 pm. \(text{T}=1.5;text{hours}=frac{3}{2};text{hours}\) \(text{S}_text{G}=frac{text{D}}{text{T}}\) \(text{S}_text{G}=frac{30;text{miles}}{frac{3}{2};text{hours}}=30timesfrac{2}{3}=20;text{miles per hour}\) \(20;text{miles per hour}=text{S}_text{C}-50;text{miles per hour}\) \(20;text{miles per hour}+50;text{miles per hour}=text{S}_text{C}=70;text{miles per hour}\)  data sufficiency question from Magoosh, then review the video explanation.[/list]   Let us know how you did on these practice questions in the comments below. If you’re looking for more GMAT motion problems, try out one of Magoosh’s GMAT plans, which comes with practice tests, video lessons, and study schedules. Good luck! The post How to Solve GMAT Motion Problems appeared first on Magoosh Blog — GMAT® Exam. |

| FROM Magoosh Blog: Everything You Need to Know about Getting an MBA |

An MBA, or a “Masters of Business Administration,” is a postgraduate degree achieved after an MBA candidate successfully goes through a business-focused program, usually lasting 1 to 2 years, and can be full-time or part-time. MBA programs are intended to better prepare you for business management skills and to make graduates more competitive in applying for leadership roles, or to crack into popular and high-paying industries, like tech, high-finance, and consulting. Check out our answers to frequently asked questions about the MBA below! What Is an MBA? [*]What Are the Benefits of an MBA?[*]What Do MBAs Cost?[*]How Hard Is an MBA?[*]Who Is an Ideal MBA Candidate?[*]How Do I Apply for MBA Programs?[*]When Should I Start Applying for an MBA?[/list]  full-time and part-time MBA as both went through the same academic rigors. Online MBA Programs This is the broadest category here, as “online MBAs” could very well be EMBAs, full-time or part-time. Generally, the feature is in the name: it’s online, rather than in-person, but there are some hybrids. Scholarships, as noted above, are more plentiful for full-time in-person programs. Your mileage here will vary depending on the university, as many programs have deep wells of experience in facilitating connections and learning online, but others are a little newer to the scene and adapting to the increasing trend to move online.